The introduction of Maastricht criteria that stipulated fiscal prudence by obliging EU member states to adhere to the level of public debt below 60 percent of the GDP and low fiscal deficit boosted the expectations of stable macroeconomic environment, partly sustained by the European Central Bank which, since its inception in 1999, successfully maintained price stability. Despite an enviable achievement in the stabilization of inflation expectations, the EU Treaty did not stipulate stringent fiscal rules in case of the breach of treaty obligations on behalf of EU member states, neither has European Growth and Stability Pact (EGSP) provided selective mechanisms that would hinge on the EU member state in case Maastricht criteria were not fulfilled. On the other hand, the gradual enlargement of the European union did not finalize in the economic union characterized by the realization of four basic freedoms.

For years, Italy and Greece have repeatedly breached the Maastricht treaty in the fiscal sense. Prior to adjoining the European Monetary Union, Greece repeatedly experienced volatile inflation rates and default on its external obligations and subsequent Drachma depreciation. Italy’s macroeconomic stabilization hinged on the discretion of government spending which, after excessive rises under various transition governments, cumulated in one of the highest debt ratios within the EMU. How could EMU countries, despite a stringent set of rules delineated by the Treaty of Maastricht, pursued discretionary fiscal policies and jeopardized the macroeconomic stability of the national economies and the Eurozone?

The asymmetry in political structures and underlying macroeconomic fundamentals across member countries casts significant doubt in the long-term stability of the Eurozone as an area with common monetary policy. The necessary condition for the inception of common monetary policy does not hinge on the political initiatives that pervaded the process of European integration but on the careful consideration whether adjoining countries adhere to the macroeconomic criteria as denoted by the Maastricht Treaty. The failure to adhere to the contours of fiscal prudence and budgetary discipline by the major EU member states, with few notable exceptions such as the Netherlands, Austria and Finland, lies at heart of the underlying reasons why significant asymmetry and non-coordination in fiscal policy resulted in the adoption of dispersed economic policies whereas the adverse outcomes were not foreseen neither by the politicians neither by policy advisers and academics.

The non-coordination of fiscal policymakers was highly evident in the division of member states on the core countries and EU periphery. Considering the peripherical countries, Italy, Spain, Portugal and Greece repeatedly proved ill-disciplined in managing the levels of public debt and the magnitude of the budgetary imbalance. Portugal is often the case in point. Prior to the introduction of the Euro, Portugal experienced unprecedented economic boom. Between 1995 and 2001, economic growth averaged 4 percent per annum and the unemployment rate reduced from 7 percent to 4 percent by the end of 2001.

However, fiscal policymakers in peripheral countries repeatedly produced ill-conceived fiscal mismanagement of public finances. In 2008, the level of budgetary deficit in Greece exceeded 13 percent of the GDP whereas the country has not adhered to Maastricht criteria ever since the introduction of the Euro. After the depreciation, the net debt as percent of GDP in Greece reached 85 percent of GDP and increased to 110 percent of GDP by the end of 2008. As IMF’s recent forecasts suggest, by 2012, Greece’s public net debt could reach 175 percent of GDP.

A natural question is whether the exclusion of peripheral countries from the Eurozone might be feasible and whether Greece’s default on external obligations might help overcome country’s mountainous strain on public debt. First, the re-adoption of domestic currencies is hardly a solution to overcome the intricacies of debt crisis. If Greece re-introduced drachma, external obligations would be strained by a painful and enduring bank run since investors would withdraw the deposits from the portfolio and invest it into safer holding with less volatility and uncertainty ahead. Another argument in favor of Greece exiting the Eurozone is that a devaluation of drachma would boost inflationary expectations and consequently reduce the burden of the public debt but given junk score on government bonds, a rather immediate bank run would follow the devaluation of drachma rather than macroeconomic stabilization.

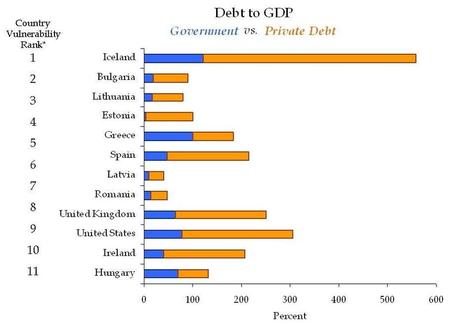

The question is whether non-coordination between European fiscal policies helped facilitate over-leveraged financial sectors which asked for the bailout by central governments in the wake of the 2008/2009 financial crisis. Over-leveraged financial sectors were attributed to the determinants of various extent. Some argued that over-leveraging is the outcome of innovative financial engineering where fancy mathematicians and physicists applied VaR models to calculate the probability of losses in the portfolio distribution of returns whereas the financial derivative schemes developed by advanced and complex mathematical models were so complicated that nobody, sometimes even mathematicians themselves, could understand sensibly.

The solution to revive the Eurozone economy and revive it from a decade of flawed political imperatives should not exclude multiple options. The focal point of the Eurozone’s recovery from debt crisis should be to help peripheral countries establishment fiscal prudence, discipline and soundness of the public finances. In fact, the recovery from the debt crisis will endure for more than a decade. The structural adjustment does not rest on the ability of the EU to provide financial assistance to peripheral countries but on the principled and coordinated action to reform inefficient public sectors which are at the heart of the debt spiral since years of generous entitlements to civil servants have tremendously raised the net present value of public debt to the point that peripheral countries are on the brink of default on its external obligations. Without generating substantial fiscal surpluses, there is no feasibility and no realistic scenario under which public debt level would be brought under the control in the near-term perspective. Hence, recent discussions of the consequences of debt crisis in Europe have simply overlooked the importance of growth-enhancing measures as the real cure for growing debt-to-GDP ratio where the measures do not apply to peripheral countries only.

First, in the wake of fiscal insolvency of public pension systems, effective retirement age should be raised substantially for men and women alike. The studies have shown that under the increase in effective retirement age to 65 years, long-term fiscal obligations would reduce and consequently an important step towards long-term macroeconomic stability would be achieved. Nearly every European country is facing low-fertility trap followed from increased affluence and generous early-retirement policies from 1970s onward. Consequently, European government have amounted a mountain of net financial liabilities that exceeded the size of GDP by several times, respectively. Decreasing the size of net liabilities to contemporary and future generations of retirees, requires a robust increase in effective retirement age. Higher retirement age threshold would substantially increase working-age population by encouraging labor market participation among the elderly. Current levels of effective retirement age are unsustainable in the long-run since a growing burden of pension obligations can seriously threaten the stability of the public finance and increase the probability of fiscal insolvency.

Second, European countries suffer from low productivity growth. In some countries, such as Italy productivity growth has remained stagnant over the course of recent two decades while elsewhere productivity growth is to slow to compensate for the increase in nominal wage rates. The evidence, in fact, overwhelmingly suggested that high tax rates are the prime obstacle to greater labor market participation, particularly among the elderly who face high implicit tax rates on work. In particular, to facilitate the channels of productivity growth, marginal tax rates should be decreased substantially. At current levels, marginal tax rates restrain labor supply significantly. In the Netherlands, the top marginal income tax rates reached 52 percent in 2011 which is a serious hinder on the working activity. In this respect, bold tax reforms should be complemented with more flexible labor markets which remain saddled with employment regulations and distort labor supply incentives. Less regulated labor market to supplement greater labor force participation, especially among women, elderly and the youth is vital to enhance productivity growth since living standards by the end of the day are determined by productivity improvements.

Ultimately and most importantly, peripheral countries should be given a free choice whether to withdraw from the EMU since recent financial crisis has shown that Eurozone is a suboptimal currency area which emerged from non-cooperative fiscal policies among its member states that caused adverse outcomes and asymmetric adjustment where macroeconomic stabilization outcomes are mutually exclusive among member states. Asymmetry adjustment that currently threatens the existence and stability of Eurozone lies at the heart of Eurozone’s debt crisis. As a general matter, economic policies have failed to recognize that structural measures in the labor market and fiscal policy regime could facilitate growth enhancement and provide the necessary impetus to stabilization of crisis-impeded monetary union. Recent suggestions by France and Germany for EU member states to form a fiscal union have led to sustained resistance from the UK which dissolved from the fiscal pact.